IPF – Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

This factsheet explains what IPF is, and how it can be diagnosed, treated and managed.

What is IPF and who is affected?

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or IPF is a long-term (chronic) lung disease. IPF is part of a large group of diseases that cause scarring of the lungs (this is called fibrosis). The diseases that cause scarring of the lungs are called interstitial lung diseases (ILD).

IPF usually affects older adults and is rare in people under the age of 50 years. The disease is more common in men than women.

IPF is a progressive disease, which means that it gets worse over time. This is because the scarred lung tissue in someone with IPF is less able to work normally. Some people get worse very quickly, whereas others remain relatively healthy for a longer period of time.

Some online information reports that people diagnosed with IPF can expect to live for 3 – 5 more years after their diagnosis. However, these numbers date from a time when there were no treatment options for people with IPF. Life expectancy for people with IPF may be different now, but average life expectancy from diagnosis is not known. It is important to note that life expectancy varies from person to person and depends on many factors. These include age, disease stage and treatment.

There is no known cure for IPF, but treatments are available to slow down the disease progression and to help manage the symptoms effectively. For a small group of patients, lung transplantation may be an option.

What causes IPF?

Scientists do not know exactly why some people develop IPF, but it is thought to be due to a combination of a person’s genes and what they have breathed into their lungs throughout their life. Some research suggests that IPF is a form of early aging of the lungs.

Many people living with IPF have smoked in the past, but it is not known if smoking cigarettes is a direct cause of IPF. There is also increased risk of developing IPF for people who have worked in certain jobs, including metal-working, wood working and farming. This could be because a person may have breathed in certain particles or chemicals in these jobs.

IPF can also run in families – around 1 in 20 people with IPF has a relative who also has the condition.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of IPF can vary between people and develop over time. Not every person with IPF will have all of the symptoms listed below, and having these symptoms does not mean that you have IPF. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about symptoms like these:

Breathlessness

Feeling out of breath when doing physical activities that you would not usually find too difficult.

Coughing

A cough that lasts for longer than a few weeks. The cough might be quite severe, painful, or cause you to retch (a cough that feels like you are going to be sick).

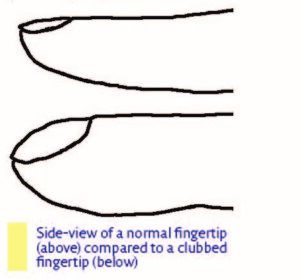

Clubbing (swelling) of the finger tips

Some people with IPF notice changes at the ends of their fingers, known as clubbing. These changes can include the nail curving more than normal when looked at from the side, and the fingertips getting larger.

IPF complications

One severe complication of IPF is having an ‘acute exacerbation’, which is when your symptoms get much worse in a short space of time. You should contact your doctor as soon as possible if you think your symptoms are getting worse quickly. Your doctor or healthcare professional will screen you for this complication and if needed you may be hospitalised for supportive care. Unfortunately, no good, proven treatment for acute exacerbation of IPF currently exists.

Other conditions

Some people with IPF will also have other conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (narrowed air tubes) or emphysema (damage to the air sacs in the lungs), acid-reflux, lung cancer, pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs), sleep apnoea (pauses in breathing while you sleep) and coronary heart disease.

“IPF has changed my life. I need to manage my strength and my time more.”

Guenther, Austria

Steps to diagnosis

IPF is a rare disease, and it can be difficult to diagnose because it has the same symptoms as many other lung conditions, and some other conditions like COPD, asthma and heart failure. It is important that IPF is diagnosed as early as possible, so that treatment can start early. When you first go to see your doctor, they may listen to your chest using a stethoscope. One of the signs of IPF is a chest sound known as ‘velcro crackles’, which can be heard through a stethoscope. Your healthcare professional will also ask you about your medical history to see if another condition could be causing your symptoms. They may also discuss your case with other experts. To be able to correctly diagnose IPF, your doctor can refer you to a pulmonologist (specialised lung doctor) and they may choose to run some of the following tests:

CT scans

You may have a CT scan (a type of scan that uses x rays and a computer to create a detailed picture of the inside of the body), or a high-resolution CT scan (HRCT). The doctor will use these scans to look for evidence of fibrosis (scarring) in your lungs.

Blood tests

Blood can be used in lots of different tests to look for signs of disease. Your doctor might take some blood from you to see if the level of oxygen in your blood is low, or to measure levels of proteins that are linked to IPF.

BAL fluid testing

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is a procedure that involves passing a tube with a camera (bronchoscope) through the mouth or nose and squirting some fluid into a small part of the lung. This fluid, known as BAL fluid, is then collected and looked at under a microscope to see if the cells that were picked up by the fluid look healthy.

Lung biopsy

A lung biopsy involves collecting a small part if the lungs (some tissue) for analysis. This can be done by passing a tube with a camera (bronchoscope) through the mouth or nose to collect the tissue. It can also be done as a surgical procedure, so you may have a short stay in hospital. If you are diagnosed with IPF you will be told how advanced your disease is. This can help you know what to expect, and to plan for the future. It will also help your doctor to talk to you about what treatment and management options could help you the most, whilst taking your circumstances and preferences into account.

Treatment

Doctors will discuss your symptoms, stage of disease and overall health when deciding which treatments may be the best to offer you. Not all of the treatments described below are available or used in all European countries. If you have any questions about these treatments, please discuss them with your doctor:

Anti-fibrotic drugs

Anti-fibrotic drugs are available to treat IPF. These drugs slow down the rate of fibrosis in the lungs and can help you live longer.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are drugs that reduce swelling. Your doctor will avoid using them to treat IPF because they can sometimes make IPF worse, especially in high doses. However, they may be used in the short term during an acute exacerbation or to help manage a severe cough.

Vaccinations

It is important to stay up to date with your vaccinations as people with PF tend to suffer from respiratory infections. You should speak to your doctor about regular flu, pneumococcal and COVID-19 vaccinations. Record dates of jabs so you know when you are due to have a booster vaccine.

Physical activity and pulmonary rehabilitation

Regular physical activity can improve IPF symptoms and overall wellbeing. Your doctor will be able to advise you on the level and type of physical activity that could benefit you the most. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a programme of exercise and education designed to help people with lung conditions to manage their symptoms. Pulmonary rehabilitation can improve your physical strength and reduce the impact of IPF on your life. It is also an opportunity to meet and talk to other people living with lung conditions.

Oxygen

You may be offered medical oxygen to help you to breathe, particularly if the level of oxygen in your blood is low when you are resting or if your oxygen levels drop too much when you are active. Depending on how advanced your IPF is, you might use oxygen all the time or only when you are doing physical activity.

Treatment of other diseases

People who have IPF often have other diseases as well. Some other conditions like emphysema, asthma and coronary heart disease can make your IPF symptoms worse, so your doctor might screen for other diseases and provide treatment for these if necessary.

Lung transplantation

If you are otherwise healthy, you may be eligible for a lung transplantation (an operation where your own lungs are replaced with healthy lungs from a lung donor). Lung transplantations can involve one lung or both lungs. However, this treatment is not always an option because of the shortage of donor lungs available worldwide and age restrictions for lung transplants.

“Exercise – I don’t do as much as I should, but I do a little bit of walking because I believe that’s important, as well as getting fresh air.” Peter, England.

Continuing care

Stopping smoking

Smoking cigarettes is linked with IPF and causes many other diseases. Your doctor will recommend that you stop smoking completely to protect your lungs and improve your overall health. They should also be able to help you consider how to increase your chances of stopping, for example by prescribing medication like nicotine replacement therapy or helping you to find a support programme.

Avoiding infections

For people with chronic lung conditions like IPF, avoiding lung infections (for example flu, COVID-19, Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or pneumonia) is important. This is because your breathing becomes even more difficult when you have a lung infection. Here are some things you can do to help reduce the risk of getting an infection:

- Wash your hands frequently with warm water and soap. This is particularly important before eating and after visiting public places.

- Ask friends and family to wait until they have fully recovered from a cold or flu to visit.

- Avoid sharing household items, like cups and towels, with other people.

- Ask your doctor or specialist nurse about getting the flu vaccination before the flu season (December – March) starts. This vaccine helps to protect against some of the causes of flu.

- Talk to your doctor about pneumococcal vaccination, which protects you against several different infections that can lead to pneumonia. See the section above regarding other vaccinations you may be offered.

Monitoring

Your doctor or specialised centre may invite you to regular monitoring or ‘follow-up’ appointments to see how you are doing and if your treatment and management plan needs adjusting. These appointments might involve doing some more tests. If your symptoms get much worse in a short period of time, you should not wait for your monitoring appointment – contact your doctor, specialist centre or specialist nurse immediately.

Palliative/supportive care

Palliative or supportive care is care provided for people with chronic conditions, whose symptoms are severe and significantly affect their wellbeing. The aim of palliative care is to help people live with their symptoms, make them more comfortable and improve their quality of life. End-of-life care is a type of palliative care. It can include comfort care (such as options to manage pain and other symptoms) and emotional support for people who are approaching the end of their lives. You may find it helpful to discuss palliative care and end-of-life options with your doctor or specialist nurse before you need to access these types of care.

“Life may slow down a bit, but there still may be a lot of joy in the years to come. Find fellow people with whom you can share your everyday problems… You can get honest answers to your questions and useful experiences from others.” Maria, Hungary

Living well with IPF

Many people who are diagnosed with IPF find that the disease is on their mind a lot of the time. You and your loved ones might find it difficult to think about how IPF will affect your life, and to come to terms with living with a terminal disease.

Talking to other people with experience of this disease can be very helpful. There are lots of IPF patient groups across Europe that can put you in touch with other people who have IPF. Ask your doctor or specialist nurse for details of your nearest group, or use the ELF Patient Organisation Network search on the European Lung Foundation website.

Having a good social support system at home can also help make living with IPF easier. In particular, family members and close friends can provide valuable practical and emotional support.

Research and clinical trials

If you are interested in taking part in research to help scientists investigate IPF and IPF treatments, you may be able to join a clinical trial. If you are interested in learning more about local trials that could suit you, talk to your doctor. They will be able to advise if there is a trial that is appropriate for you to join, taking your medical history and current health into account.

Further information

EU-IPFF | www.eu-ipff.org The European Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Related Disorders Federation (EUIPFF) is an organisation that brings European IPF patient organisations together. EUIPFF works to raise awareness of IPF, call for better access to care, and bring hope to people who are living with the disease.

ERN-Lung | www.ern-lung.eu ERN lung is an EU-funded project that builds and maintains a clinical care network for rare lung diseases, including IPF.