Lung cancer

Lung cancer is a cancer of the windpipe (trachea), airways (bronchi) or lung air sacs (alveoli). This page will look specifically at the two main types of lung cancer that occur most often.

Content Table

The two main types of lung cancer are:

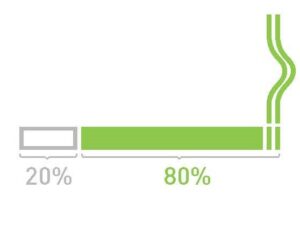

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which typically accounts for 80 out of 100 lung cancer cases (or 80%). The most common forms of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Rarer forms are covered in our rare lung cancers factsheet.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Around 20 in 100 lung cancer cases are SCLC.

Information on mesothelioma is covered on another page. This is a type of cancer that grows in the lining around the lungs and is usually caused by breathing in asbestos dust. Read more about mesothelioma and other occupational lung diseases.

There are further subtypes of lung cancer that do not happen very often and are considered ‘rare’.

Risk factors

While smoking tobacco is linked to more than 80% of all lung cancer cases, people who have never smoked or been exposed to passive smoking may develop lung cancer. See our information on the risk factors for tobacco smoking and passive smoking.

Other causes include exposure:

- To air pollution (including diesel exhaust fumes)

- At work or during hobbies (to asbestos, wood dust, welding fumes, arsenic, industrial metals e.g. beryllium and chromium)

- To indoor air pollution (radon, coal smoke)

There may be other causes, and more will likely be found in the future. Having the following conditions can also increase your risk of developing lung cancer:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Head and neck, and esophageal cancer (sharing the same risk factors like smoking)

- Lymphoma or breast cancer (treated with thoracic radiotherapy)

- Lung transplant recipients

- Genes can also play a role in some lung cancers. If there is a history of lung cancer in your family, you could be more likely to develop the condition, but this is not the same for everyone.

Symptoms and signs

The most common symptoms and signs of lung cancer are:

- Long-term cough (lasting more than 3 weeks)

- Coughing up blood, or flecks of blood, in phlegm

- Losing weight for no reason

- Being out of breath for no reason

- Not feeling hungry

- Extreme tiredness (fatigue)

- Pain in the chest

- Pain in the bones

- Pain in the shoulder

- Swelling in the neck

- Muscle weakness

- Hoarseness (weak, raspy or strained voice)

- Repeated chest infections that don’t respond to medication

Early symptoms are often not picked up as they are linked to other common conditions. Some people do not have any symptoms at all. When lung cancer is picked up earlier, there are more treatment options available. Visit your doctor if you have any concerns, particularly if you are at a higher risk – see the ‘Risk factors’ section.

Lung cancer screening

Lung cancer screening is the process of using tests to find the disease at an early stage, before symptoms are present.

Diagnosis

“When the doctor tells someone they have lung cancer they will find it almost impossible to take in any further information. It can be good to have a carer or someone to accompany you so that they can be your ears.”

Dan, Ireland, caregiver

Generally, the process of being diagnosed with lung cancer is as follows: An X-ray and a computerised tomography (CT) scan (where your body is X-rayed at a number of angles before a computer puts together a detailed image) of your chest will first be done to show if there is a lung tumour. Your doctor may confirm the diagnosis of cancer by taking some samples of the cells from your tumour and testing them (this is called a biopsy).

A biopsy can be carried out in a number of ways, most of which are done as an outpatient (you do not stay over):

- Using a camera that goes inside your lungs called a bronchoscopy. This is a flexible tube that has a video camera at the end (called a bronchoscope). The tube is inserted through your nose or mouth. You will receive a sedative to relax you and a spray to numb your throat. See our bronchoscopy factsheet for more information.

- Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) – this is similar to a bronchoscopy. The bronchoscope is fitted with a small ultrasound probe to help guide the physician to the right area to take a sample. This area is usually the area between the two lungs where your glands sit (called mediastinum).

- CT-guided biopsy (where you go through the CT scanner and the X-ray images guide the physician to the right area).

- US (ultrasound) guided biopsy (where the physician uses an ultrasound device to identify the right area and inserts a needle in it to take a biopsy. Local anaesthetic is used to numb the area where the needle will be inserted)

- Surgery – where a surgeon obtains a biopsy generally in the least invasive way possible. This is using a thoracoscope, a traditional incision or a robot. The procedure is performed under general anaesthesia and a chest tube remains in place for a few hours or in some cases days to re-expand the lung.

Finding out which stage your lung cancer is at

If your doctor believes that you have lung cancer, they will request some tests that can show how far the cancer has spread. Staging tests also give useful information about the best place to collect a sample of tissue from. The stage of your lung cancer is one of the factors that will help your healthcare professionals to decide on the best kind of treatment to offer you. This process is called staging and could involve a positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan. This is when a CT scan is combined with a PET scan, which involves a small amount of radioactive dye being injected into your veins to show up anything abnormal in your tissues. Or it could involve further CT scans of the stomach area (abdomen) and brain and a bone scintigram, depending on availability of tests. On some rare occasions, your doctor may suggest that you have a biopsy of your axillary (armpit) and neck lymph nodes.

Your doctor will be able to give you information on the stage of the cancer. This is based on tumour size, if it has spread to your lymph nodes/glands, or if metastases are present). This staging process is sometimes referred to as TNM (tumour, node, metastasis).

Being told that you have lung cancer can be devastating. Many people with lung cancer have told us that being able to talk to someone outside of their family, such as a counsellor or psychologist, can often help. If you feel this might be helpful for you, talk to your doctor about what services might be available – see the ‘Feelings’ section for more about this.

Prognosis

Lung cancer is a serious illness. In recent years, there has been a vast increase in treatment options and lots of work is being done to help people live longer and with a better quality of life. Most prognosis information is given in terms of a ‘5-year survival rate’. This term is often used by healthcare professionals and refers to the number of people who lived for 5 years or more after being diagnosed with this type of lung cancer.

It is important to remember that everyone is different and your tumour may not respond to treatment in the same way as another person’s tumour. Statistics do not necessarily reflect what will happen to you. You should see your prognosis as a guide – and discuss it with your healthcare professional.

“Don’t just look at the statistics. You are not a number and it is very important to balance out all the negative information by looking at positive websites that can give you hope.”

Tom, UK, individual with lung cancer

Treatment

“It is very important that everyone has hope from the moment they are diagnosed, and there are new treatments coming along all the time. The treatment that I am on was not available three years ago, and now it is old-fashioned, so do not give up hope.”

Tom, UK, individual with lung cancer

There are several different types of lung cancer, requiring a range of different treatments. Your treatment plan will be based on the type and stage of lung cancer you have, your general state of health, and your personal preferences. Treatments may be focused on either curing your lung cancer (curative treatments), or on helping you live longer and with a better quality of life with lung cancer (palliative treatments).

-

Multidisciplinary teams

In some European countries, the decision to treat, and the type of treatment, is discussed among a panel of experts in the field, called a multidisciplinary team (MDT). An MDT usually includes:

- A respiratory doctor (specialising in lung health)

- A thoracic surgeon

- A medical oncologist

- A radiation oncologist

- A radiotherapist

- A pathologist (doctor who will examine your biopsy and decide your type of cancer)

- A radiologist (specialising in lung imaging)

- A nuclear medicine specialist (specialising in PET CT reporting)

- A molecular biologist

- A palliative care physician (specialising in looking after people in pain and disability due to their lung cancer)

- A psychologist

- A nurse (specialising in lung cancer)

MDTs are becoming more common in the treatment of lung cancer. However, in some countries, they would not include all the experts mentioned here. If you are managed by an MDT, you will normally have one or two healthcare professionals as your main points of contact, and you may visit other healthcare professionals for specific treatments.

There are many countries where the decision to treat relies on a single doctor, usually a lung health specialist, often called a pulmonologist, respiratory physician or chest physician.

-

Surgery

If you are fit enough for surgery, and your tumour has not spread beyond the lungs, you may be offered an operation to remove the tumour.

Surgery is mainly used to treat non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at an early stage. However, if you are diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) at a very early stage and it has not spread, some doctors may suggest surgery. If your cancer has spread, then surgery is unlikely to be the right treatment for you.

The lungs are made up of different sections or ‘lobes,’ with three in the right lung and two in the left lung. The usual operation for lung cancer is called ‘lobectomy’. The surgeon will completely remove the part of the lung (lobe) which contains the cancer and the glands around the lung (lymph nodes) to which cancer can spread. Sometimes, a smaller part of a lobe is removed and this is called a ‘segmentectomy’ or a ‘wedge resection’. Occasionally, the entire lung is removed completely (pneumonectomy). The extent of resection depends on tumour size, the breathing tests before surgery, a person’s performance status and general state of health.

You will receive medication to make you fall asleep (general anaesthetic) for the duration of these operations and be given pain medication following the operation.

Before surgery, you may receive chemotherapy or immunotherapy in order to shrink the tumour as much as possible before the operation. This makes it easier to remove surgically. Sometimes radiation therapy is offered prior to surgery as well.

New surgical techniques have been developed to try to remove the cancer. These are less invasive, which means there is less damage to your tissue during surgery. This includes a type of keyhole surgery known as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), in which a small video camera and instruments are placed through small cuts into your chest to guide the surgeon during the operation. Recovery time for keyhole surgery is quicker, so may be a possibility for more people.

In some centres, robotic surgery is offered in which a small video camera and multiple instruments are placed through several small cuts into your chest and these are managed by a robotic device which is in turn guided by the surgeon. In this case, the surgeon has no direct contact with your chest but they manage it through the robotic device. This approach is not a standard of care as yet but may be offered by some centres.

Surgery is not always the best option for everyone – it could be better to treat your lung cancer with systemic therapy (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted agents or combinations), often depending on where the tumour is and the stage of cancer. Your healthcare professional will discuss your treatment options with you.

-

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to treat cancer. It works to slow down the growth of the tumour and to kill cancer cells elsewhere in the body.

The drugs can be given over different lengths of time and either injected directly into a vein or through an intravenous drip or pump. Some are also delivered orally (by mouth), as a tablet. You will usually receive the chemo as an outpatient at the hospital every 3 or 4 weeks.

Most chemotherapy drugs cause side-effects, and nausea (feeling sick) and sickness are the most common. Anti-nausea drugs will be given to help with this. Other side-effects may include hair loss (regrows after treatment has ended), feeling more tired than usual, losing your appetite or changes in your sense of taste. Medications are available to help treat these side effects.

Chemotherapy affects people in different ways, so it is hard to say how you may be affected in advance. Many people are able to carry on with their normal activities during their treatment.

Just as patients with different types of lung cancer respond differently to surgery, it is possible to tailor chemotherapy depending on the type of tumour a person has.

As experts have understood more about the biology of lung cancer, they have also been able to develop new drugs that target specific types of cancer. These are called biological therapies or targeted therapies.

Depending on your type of lung cancer, your biopsy will be further tested to see if you may benefit from specific targeted therapy.

-

Targeted therapies and immunotherapies

Targeted therapies for specific types of lung cancer come in tablet form, e.g. EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) inhibitors or ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) inhibitors. These drugs work to block the growth of cancer cells and can control this for a long time. You take the tablets at home, rather than having to travel to a clinic as you would for chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment. Targeted therapies tend to come with fewer side-effects than other types of treatment.

Not everyone will benefit from targeted therapies, as this depends on the type of tumour you have. Access to these drugs may also depend on your own country’s recommendations for lung cancer treatment and funding by national health care systems.

Immunotherapy (a type of biological therapy) is a treatment approach that works by enhancing our natural immune system to fight cancers.

To find out if your type of lung cancer could be treated with a targeted therapy, you will need a molecular diagnostic test. These tests look at biological markers in a tissue sample of your tumour and help to find out more information about whether a particular drug or targeted treatment would be likely to work for you. A liquid biopsy looking at molecular alterations in your blood may also be used to guide therapy in selected cases.

This test could happen at the time you are diagnosed, or at a later stage in your treatment. Talk to your specialist to find out if molecular testing is an option for you.

-

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can be offered either as a standalone treatment, or given after surgery or in combination with chemotherapy. There are many different forms of radiotherapy, using different techniques, doses and timings.

If your tumour is at an early stage and you are not able to have surgery (if your lungs are not working as well as they should do or you have other significant diseases that increase the risk of surgery) you may be offered modern radiotherapy called SABR (stereotactic ablative radiotherapy). This is almost as effective as surgery and also reduces the damage caused to the areas surrounding the tumour.

Radiotherapy uses high-energy X-rays to destroy the cancer cells. You typically receive this treatment every day, 5 days a week, for about 6 weeks.

You do not need an anaesthetic and receive the treatment lying on a table while the machine that delivers the radiation (a linear accelerator) moves around you at different angles.

Short-term side effects may include skin inflammation (swelling and soreness), sore throat and trouble swallowing, cough and breathlessness. Most people do not have any long-term side effects, although some people can get swelling and soreness in their lungs (called radiation pneumonitis), which is treated with steroids.

If you have undergone surgery to remove your tumour, then you may also receive radiotherapy as an additional treatment after surgery to make sure any remaining cancer cells are killed.

Sometimes radiotherapy is also prescribed to help with symptoms, such as treating blockages in your windpipe to make it easier to breathe. This type of radiotherapy is the more usual type and is not as highly targeted as other forms of radiotherapy. It is usually offered as a standalone treatment or in combination with chemotherapy. In some cases, you may be offered radiotherapy to treat areas outside your lungs, such as the brain or bone, if the disease has spread.

-

Palliative care

Palliative care (also called supportive care) aims to improve the quality of life of people affected by serious illnesses such as lung cancer and their family members.

Palliative care will not cure the condition, but it can reduce and treat the symptoms and side-effects experienced. It is offered alongside other treatments.

Sometimes palliative care can be minimally invasive, including treating airway blockages with stents or laser using a bronchoscope.

Accessing palliative care services can help people affected by lung cancer to live their lives as best as possible.

Palliative care can be accessed at any stage from diagnosis onwards and can provide relief from pain, nausea and other symptoms, and offer support and comfort to people affected by lung cancer. It involves caring for people’s physical, emotional and spiritual needs in the best way possible.

Palliative care can be provided in many settings, such as hospitals, communities, or hospices. Finding out what palliative care support is available for you can help you make decisions about how you want to be cared for now and in the future.

Talk things through with any of your healthcare professionals. Ask questions and tell them about any concerns you have now and for the future. You may also want to talk things through with your family and friends. If they know how you feel they might be better able to support you.

“Attending the day hospice has helped my breathlessness tremendously and the pain is now also much better. Talking with the palliative care nurse has helped me see that I still have a lot of life in me and now I look forward to every day again.” Mary, Ireland, individual with lung cancer

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are a form of research that help to evaluate how well drugs work for different people. They often include potential new treatments and can be a form of treatment, particularly when other conventional treatments are not an option.

There are many lung cancer clinical trials taking place in Europe. Talk to your healthcare professionals if you want to find out more about taking part in a trial. You can find out more information on the links below:

Learn more about the ELF Lung Cancer Patient Advisory Group

If you have lived experience of lung cancer and you would like to help improve diagnosis, treatment and care, learn more about our Lung Cancer Patient Advisory Group and how to get involved.

Learn moreLiving with lung cancer

“I mostly distanced myself from my emotions: there was anxiety, but I did not let this through. I was emotionally suspended, frozen, and focused on what had to be done. I did not cry as I felt once I started, I would not be able to stop.”

Margaret, UK, individual with lung cancer

Feelings

Having lung cancer can affect you emotionally as well as physically. You may find that you experience negative, upsetting and confusing feelings.

It is important to remember that you are not alone in what you are going through. There are many online and in-person support groups for people in your position where you can talk about and hear other people’s experiences with lung cancer and build up your own support group.

You may find it helpful to talk to friends and family about the way you are feeling. Their feelings may be similar or different to your own.

It may also help to speak to a counsellor or psychologist for some support with dealing with your feelings. Sometimes it is easier to talk to a stranger (or you may not have friends and family around to support you). A counsellor/psychologist can give you space to talk and think about how you feel.

Ask your doctor to provide some guidance on dealing with your feelings and if there is any access to psychological support.

“Cancer is an illness which you may live with or which you may overcome. I believe that a positive attitude to your treatment and trust of your doctor may make miracles.” Natalia, Poland, individual with lung cancer

“Enjoy every day. I was always working too hard, but now that fatigue has slowed me down, I am spending more time with my family. I am also aware that my energy levels can drop off, so I am much more aware of having rest periods during the day.” Tom, UK, individual with lung cancer

There are a number of things you can do to help yourself on a daily basis:

Stop smoking

If you have been diagnosed with lung cancer and smoke, quitting smoking can improve your prognosis and quality of life.

Eat a healthy diet

Try to eat a diet that helps you maintain a healthy weight and gives you all of the nutrients your body needs (protein, fruit and vegetables). You may find that certain foods make the side-effects of your treatment worse – in this case, try to avoid these. Talk to your healthcare professional if you need advice on this.

Exercise

Physical activity has been shown to be very beneficial for people with all stages of lung cancer. Try to be as active as possible when you can – for example, walking to the shops rather than driving; yoga, or swimming.

Do things you enjoy

Try to keep doing things you enjoy, e.g., shopping, visiting friends, and travelling.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

You may, especially if you have other lung health issues, be offered pulmonary rehabilitation as a way of improving your physical strength and reducing the impact of your symptoms on your life.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a type of treatment that aims to reduce the physical and emotional impacts of a lung condition on a person’s life. It is a personalised programme that combines exercise training with education about ways you can help keep yourself as healthy as possible. See our pulmonary rehabilitation page for more information.

There is some evidence that pulmonary rehabilitation before and after surgery for individuals treated for lung cancer is both possible and effective. It can help to reduce fatigue and enable you to cope with more exercise. You can access some programmes like this online as well as guidance for keeping active with a lung condition.

Dealing with practical issues

You may also need to deal with practical matters relating to your work, finances and social activities.

Making a list of questions to ask your doctor or specialist can help you manage these things and find out what support may be available to help you.

“My work-life balance became far more important and I’m very lucky as I now work part-time and spend a lot more time with my family. You still need to pay the bills, though, and I have found a happy compromise.” Tom, UK, individual with lung cancer

Patient stories

Hear from patients with lung cancer as they discuss a range of issues from clinical trials to lung cancer screening.

Patient experiencesMyths around lung cancer

With so much information on the internet, sometimes it is hard to find the truth. Here are our top 5 lung cancer myths debunked.

"Being diagnosed with lung cancer is a death sentence"

Advances in research mean that new treatments are coming along all the time and have helped to increase how long people with lung cancer live for.

How long an individual person will live depends on many things.

If the cancer is caught early enough it may be curable, and even if it is not curable, it is still treatable and many people live with lung cancer for several years.

“Only people who smoke get lung cancer”

Although smoking is the single greatest risk factor for cancer, not all people who develop lung cancer have smoked.

Exposure to second-hand smoke and other substances such as air pollution (including radon gas) increases the risk.

The number of people who have developed lung cancer and have not smoked varies in different studies, with the figures being 10% in one and 28% in a recent study.

“Molecular testing is not suitable for my type of lung cancer”

Molecular testing may help to find out more about the type of lung cancer tumour you have and help decide which treatment is most likely to work for you (such as targeted therapies).

If you have NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer), then molecular testing is most likely to be recommended. Sometimes there is a reason why molecular testing may not be suitable for you, so ask your physician to explain if this is the case.

“It is only a cough - why should I worry?”

The first signs of lung cancer are often a cough that does not go away and shortness of breath. If you have a chronic cough (that lasts for more than 3 weeks), get it checked out.

"I am too young to get lung cancer"

Lung cancer is more common in older people (in their 60s and 70s), but it can also occur in people at a much younger age and is diagnosed in people of all ages, e.g. carcinoid tumours can affect young people.

Useful resources

Find further resources related to lung cancer, including clinical guidelines, treatment decision aids and patient organisations, resources and forums in your own country.